Procedural Dynamic Room Generation in “ARE”

For the Global Game Jam this year, our team wanted to make a game that behaved like a personality test. It would try to determine if you liked killing enemies, collecting items, running around wildly, or interacting with the game’s inhabitants. Once the game had a handle on what you preferred, it would tailor itself to your desires. If you liked killing things, more enemies would be spawned. If you spent a lot of time in rooms opening chests, the next rooms you went to would have more in them to explore. It was immediately apparent that a predesigned level wouldn’t work, as we wanted the experience to be dynamic and different for each type of player. So, we needed some sort of procedural room generation, and we needed it fast. I was responsible for that feature, and found it so interesting that I wanted to share how I handled it.

I’ve played a lot of roguelikes, so the concept of random room generation wasn’t totally foreign to me. However, I hadn’t seen any that really impressed me. Especially not compared to the random generators that have been made for tabletop games. Some of the better ones generate traps, monsters, and loot in addition to basic rooms and corridors. In particular, the generators available on Donjon’s site are worth a look. Not only are they infinitely configurable, but their source code is (kind of) open! For traditional “dungeons”, they usually generate X number of rooms, and then connect them up with corridors. There’s generally a certain number of large, medium, and small rooms, but everything is calculated at once. This technique is powerful, and with enough tweaking, you can make some really nice looking maps without a lot of effort. Getting this version up and running in our game wasn’t difficult. All we had to do was have a large enough grid, randomly drop the rooms in, and then place cubes where the walls should be.

Fig 1. Randomly placed rooms. I didn’t bother writing code to create corridors to connect the rooms, because we had realized this wouldn’t work for us.

However, this technique wasn’t going to work for our game. Since the whole point of the game was to dynamically adjust to the player’s play style, a complete map generated at runtime didn’t make sense. We needed something that was totally dynamic, where levels could be built incrementally as needed. This gave me an opportunity to fix a problem I have with most dungeon generators. Since they were usually designed to be easy to draw on paper/wet-erase maps, rooms are usually defined in chunks of squares, either 5ft or 1m. This means walls are usually that thick, which is unrealistic (most interior walls are only ~6” thick!), and room dimensions would be defined in those increments. I wanted our rooms to be able to exist outside of a strict grid system, and to not waste a lot of space with walls. So, I built a relatively simple system.

Rather than storing a grid, I tracked two different types of objects: rooms and doors. Doors only stored their position and orientation (latitudinal or longitudinal), and the two rooms they connected. Rooms knew their position, size, and kept a list of doors that were connected to them. I had a geometry generator that could spit out walls, floors, and doors into the world, and could combine those primitives into generating rooms of random sizes. The system was designed so that if a newly generated room shared a wall with an existing room, any doors in that shared wall would automatically link to the new room.

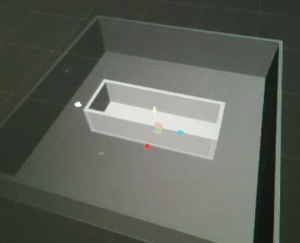

Fig 2. First test of the geometry generator, creating rooms of random sizes.

From that first step, I set about building the levels additively. I’d spawn a starting room with a single door. Then, the system would select a random door that was only attached to a single room, and generate a room that used that door as an ingress. While in-game, new rooms were only created whenever a player opened a door (that didn’t already lead to a room). Assuming that each room had at least one door in addition to the source door (and most had more), the map could theoretically expand infinitely. The rooms generated this way had a random size between two bounds, which meant that they were all relatively the same size and proportions. Besides being boring, they would often clump together, and in some cases ended cutting themselves off. So, I added a way to define different types of rooms. This controlled their bounds in each direction, which wasn’t perfect, but was effective. There were three types of rooms: a small room, a large room, and a hallway, which created very long, but narrow rooms. This worked well enough for our game, theoretically, but I decided to go just a little bit further.

Fig 3. Large rooms, small rooms, and hallways. The hallways did a good job of keeping the rooms from clumping up too much. They were also fun to run down!

The problem I found was that while the rooms were generating dynamically,they didn’t align well. Two rooms would be adjacent to each other, but would have a small gap between them. Rooms weren’t allowed to be large enough to overlap existing rooms so rather than using the generated size, the generator was just creating a “closet”. Closets are the smallest room that could be generated when a door opened, just a square room where each wall is the width of a door. So, rather than just selecting a random size from within a set of bounds, I used a new method. Whenever a door opened, the system would generate a closet. Then, the closet would inflate over a series of iterations based on the type of room it was (using the parameters from the previous method). When the room reached a size where it could expand no further, or it had finished its expansion iterations (which were limited per room type), it would project outward to see if there were any other rooms close by. If there were, it would expand just far enough to become flush with the nearby rooms. This way, if two rooms were close, and their shared wall had a door in it (which would lead to nothing), the new room would expand enough to utilize that door. If it didn’t, the door from the existing room would most likely have little space to generate a new room, and very tiny rooms were not something we wanted to see too many of.

Fig 4. In addition to linking together better, the new room generation had different colors they could be decorated with!

The maps generated with this new technique were much more interesting to navigate, as well as connecting much more fluidly. Since this was game jam code, though, it wasn’t perfect. The final expansion step only checked for rooms in cardinal directions from its center and corners. Which meant that for a larger room, it was possible that a smaller room wouldn’t be hit by any of the rays checking the expansion, causing the large room to expand even larger, overlapping the smaller room. This usually only happened if there were many small rooms built near a large room, and then a door nearby generated a large room, which was infrequent.

Fig 5. Also, all of the things the characters say are randomly generated…and hilarious.

Since it was a game jam, and I’d spent half of my coding hours working on this algorithm, I opted to leave the bug in and focus on less important things (like player interaction, pfeh). Regardless, I’m happy with how the room generation came out, and I’m interested in pursuing it further. If you’d like to check out this method of room generation, you can see it in action in ARE!

If all that was too much words for you, here’s a TL;DR version of my room generation algorithm.

- Define Room Types (small/large room, hallway, etc)

- Generate a room with a single door.

- When the player opens a door, create a closet (smallest room possible).

- The closet decides what type of room it wants to be (from the room types)

- Inflate the size of the room a random (but small) amount based on its room type.

- Repeat 5 until the maximum number of iterations has been reached (defined, again, by room type), or until an expansion would cause the room to overlap existing rooms.

- Project rays out from the corners and center in cardinal directions, to try to find other rooms that are nearby. If there are, expand slightly so the new room shares a wall with the existing room.

- Make sure that the new room has at least one door that didn’t previously exist. Otherwise, no new rooms can be generated from it, and the map is no longer infinite.

- When player opens a door that isn’t already linked to two rooms, go back to step 4.