“Interface First” Game Design

At Cipher Prime, we create games constantly. You may only see one or two of our games released a year, but behind the scenes we make games weekly — sometimes even daily. The biggest problem is always getting started. Game jams help by providing a theme, but there are so many different places you could start with creating a digital game. I have a personal style: looking at “controls”.

As a designer, I spend a lot of time taking complex interactions and stripping them down to their basic form. I love games like Quake 3, Ikaruga, and Lumines — to me, arcade games will never die. One major thing these games all have in common is that their controls are tight, sexy, and responsive. When I look at these games, it’s hard to not think the game designers took a lot of cues from their control interfaces. When I start creating a game, the very first question I ask is, “How do I want to interact with this thing?”

In many cases, I’ll design an entire game based on what I perceive to be the most direct, unique, or even absurd way to interact with a device or controller.

The way you interact with a device can change everything about your game design. In fact, the entire game can change based off one small insight about the way you interact with a thing. This is because your control interface is very tightly coupled to the inner loop: the very core of a game. In Mario, for instance, you’d define jumping, running, pouncing, firing, etc. as part of the inner loop. These are things you do often, over and over again.

On a closer look, these things are also intensely affected by the way you interact with your game. What if the jumping in Mario was based on your physical body actually jumping? Do you think you could still design levels that require you to jump from one platform to another in 0.3 seconds? My guess is that even the most physically fit players would start suffering from fatigue after just a few minutes of gameplay.

Anyone who knows me well would tell you I have a sick obsession for color theory. In fact, I regularly joke about being an Official Color Picker rather than designer. Since color means so much to me, let’s assume you’re creating a game where changing colors is the heart of the inner loop, and see how that affects the game design. Here’s some questions I might ask myself next, in no particular order:

“Do I want a fast- or slow-paced game? Turn-based or asynchronous?”

—For this game, let’s go fast paced asynchronous.

“Am I going to do something that relies on skill, intellect, or some combination of the two?”

—Intellect: who needs it? Let’s do something skill based.

“Why the hell am I making this? Is it for me or someone else?”

—Screw everyone else.

“Do I want something single player or multiplayer, competitive or cooperative?”

—In the vein of screwing people over, let’s do something multiplayer competitive.

Now that we know some of our very basic goals, let’s take a look at this color picker from a couple different interface options.

How about a simple controller like the old-school NES?

Chances are, we’re going to need the gamepad area for movement. With that in mind, that leaves us with two buttons. If we use one button, we can cycle colors. Cycling colors can be fast if there isn’t a range of more than 2-3 colors. However, when your get to 4 or more colors, you’ll have to press a button at least 3 times just to get to a specific color. Now you could easily do this, but you’d end up pretty frustrated, and it would be a slower experience. Conversely, you could map both buttons to two different palettes, which will give you up to 6 colors. This could lead to some confusion, but a diligent player will figure it out fast. With two buttons you could even move up or down a list of colors, giving you more granular control of your selection. If you’ve played Tetris, you can see how being able to spin both left and right came in handy for high level play. Another design solution could be to make one button cycle through colors, while the second button cycles through shades. This will cut down on visual confusion, but also give you at least 6 colors.

The iPad is an extremely interesting interface.

Your first instinct might be to design the color picker to have a slider. Unfortunately, this isn’t exactly an optimal design, because sliders are finicky on touch screens and they’re not typically very precise. A good go-to tactic for fast switching is direct access: divide the screen into different clickable areas for switching colors. We could have as many colors we want with the only limiting factor being the size of one’s fingers. Alternatively, we could always emulate a button from another device, such as a controller, but why would you? The iPad isn’t a controller, it’s a screen you can touch — it’s better to use that to your advantage.

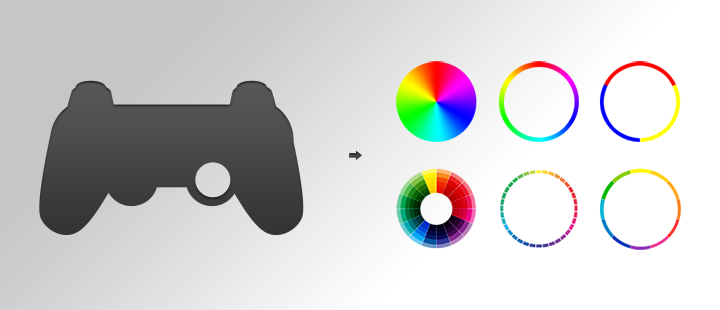

Now let’s look at the Playstation Dualshock controller.

In both arena shooters and first person shooters, one is used to using two analog sticks. What if we took that familiarity and used the second analog stick as color picker? Not only does this thought inform the design of our color wheel, it also informs the game design itself. With 360 degrees of motion as well as intensity from 0-1, we have access to a nearly infinite range of colors. This is an extremely elegant design. But is it too much? Chances are, any gameplay that hinges on selecting a color that precisly isn’t going to allow for the fast-paced gameplay we’re looking for. Thankfully, our input being both radial and analog means we can break the selection down into parts. In fact, we could adjust the size of the color wheel as we go, giving the gameplay even more breadth.

The keyboard is probably one of the most widely accessible interfaces.

The problem is it offers a ton of choices. As I said earlier, it’s a designers job to tackle the clutter; a typical keyboard might have 101 keys. We could make every single key to a color, which could certainly be fun for a typing game. If we take a cue from Quake3, we could just map the 1-0 keys as colors. If we use just 3 keys, we could play around with some pretty fun color mixing ideas.

The mouse is probably the most used interface device.

Unfortunately, it can be tragically slow when it comes to something like inventories. In many cases, designer will use menus and sub-menus to complete a challenge like this. Luckily for us, we hate making menus. It’s fairly safe to say most people have the option to both left and right click these days — even on Mac — so we could do a number of two-button options that I already presented. We’ve already thought about the Playstation controller and the radial analog selection sounds great — we could easily take this idea and adapt it to the mouse. We could use the left click to bring up the radial menu and pick the color when we release the button.

Let’s look at one final device: the Kinect.

The Kinect is a game-changer — literally. How the hell do we make color picking work when you’re just waving your hand in the air? One very interesting solution is to not actually pick colors at all. Up until this point, we’ve only thought about the possibility that the user picks the color directly. What if the game presents you with color options and you just time your actions? For instance, as the game progresses you’d see the background color change through every available color — the second it hits teal, you do a jumping jack. This idea changes everything. With this line of thought we could go back and take another look at every one of devices we’ve discussed and come up with completely new ways to interact with them and a choice of colors.

There are a million-and-one ways to start a game. This is one of the William Stallwood methods of game design. I look at control interfaces and I let them inspire every part of the inner loop. Changing the way you look at a simple action can change the very action itself and breed tremendously unique and intuitive ideas that will shape your entire game. A button can always just activate something, but it can also do so much more. At the end of the day, you’re the game designer and you’re calling the shots. Your game could always use a controller, but I urge you strongly to think about the possibility that it can’t, shouldn’t, or just might be a different game entirely.