Choosing Game Jam Themes

Every month at Cipher Prime, we hold a twelve-hour game jam, a contest in which people try to create a game based off a theme of our choosing. Along with stressing over hosting the event (and, of course, over our own jamming efforts), we stress over choosing game jam themes.

WHAT’S SO HARD ABOUT CHOOSING A THEME?

Picking a jam theme isn’t as easy as it might sound. As an organizer, you want to give jammers an interesting jumping-off point, while still letting them be creative. Oftentimes, too much freedom leaves teams paralyzed with indecision; having constraints can actually make teams think more creatively. When thinking about how much freedom a theme gives teams, it’s also important to realize that people will often self-impose restrictions subconsciously.

STICK TO TEXT

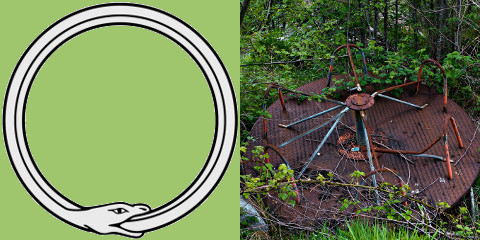

Both the Global Game Jam (GGJ) and the Philly Game Jam (PGJ) have used pictures as jam themes (below). The GGJ used a drawing of the ouroboros, and the PGJ used a photo of decrepit playground equipment.

When the games were submitted, the GGJ received lots of games containing snakes, and the PGJ received lots of games containing a playground wheel as a centerpiece. At this year’s GGJ, the theme was the sound of a heartbeat. As when the theme was a picture, many people interpreted the theme literally and submitted games that involved hearts, or love, or something else that connected very simply to the theme. While there are plenty of counter-examples to this phenomenon, anecdotally, photo- or audio-based themes lead to a higher number of literal interpretations (and fewer original games). Because these themes engage with a particular sense (sight, hearing) very strongly, people have a hard time moving beyond that strong initial engagement to something deeper. Text-based themes lack a defined visual or aural form, freeing people to think about themes abstractly, rather than concretely.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

If we’re sticking with text, generally a single word will suffice for a theme. Abstract nouns tend to give jammers plenty of context to work from without allowing them to simply utilize the theme for a set piece. Concrete nouns, however, tend to pigeonhole participants by allowing them to latch on to something tangible in the same way that picture-based themes do. Verbs, similarly, limit thinking by spoon-feeding potential player actions to designers. Conversely, single-word adjectives tend to be way too broad–it would be far too easy for designers to make any game they felt like, and then make sure that at least one tertiary aspect of the game could be described by that adjective. This is probably why the GGJ organizers have never chosen a single-word theme that was either a verb or adjective.

CATCH THAT PHRASE

Not all good themes come from abstract nouns. Another common source of good themes is catchphrases (such as GGJ’s “As long as we have each other, we will never run out of problems”). While not frequently utilized, phrases as themes can be deployed to great effect. They force jammers to consider both the literal words of the phrase, which can lead to gameplay ideas, and also the emotion and the context of the phrase, which can add many more layers of depth to consider. For instance, in 2009 the PGJ used for its theme the Michener quote, “An age is called Dark not because the light fails to shine, but because people refuse to see it.” This quote produces lots of jumping-off points, from the light/dark dichotomy, to perception of the human condition, even potentially to Dark age history. Any of these avenues could be explored and still be thematically relevant.

THEMES SHOULDN’T BE CHOSEN DEMOCRATICALLY

Textual themes are popular with the granddaddy of organized game jams, Ludum Dare (LD). LD’s community self-selects a theme for each competition. But this can lead to internal conflict. When participants get to select their own theme, they’re likely to pick a favorite theme, or one that fits a design idea they’ve had. If that theme isn’t selected, all the time they’ve spent invested in the design seems wasted, discouraging the person from participating. Additionally, having participants vote can lead to very generic themes. For instance, in 2013, LD’s theme was “Minimalism”; in 2008, LD’s theme was “Minimalist”. Having a single entity, rather than an entire community, choose a theme can prevent similar or poor themes from being chosen.

THE GOLDEN RULE: INSPIRE CREATIVITY

The point of any game jam theme is, ultimately, to inspire and cultivate creativity. Because they’re made in such a limited period of time, the games made at jams are never going to be the same as a game made over the course of several months or years. Participants shouldn’t be trying to make a generic first-person shooter, RPG or platformer. Game jams are opportunities for game creators to make something new and interesting, and game jam themes should respect that.